This page contains important information for adults teaching this curriculum. To become familiar with the curriculum please read each section linked below.

Quick Links:

- Acknowledging a Complicated History

- Introduction to the Curriculum

- Teachers Should Know

- Recommended Prior Student Knowledge

Foreword

The Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs (VCNAA) was created in 2010 through 1 V.S.A. § 852. The Commission is tasked with a number of activities related to the well-being of Native Americans throughout the state. One of those responsibilities is that of education of both Native American people and all Vermonters regarding the history and culture of the state’s Native American population.

We recognize that in today’s world, people are very mobile and that Vermont is home to people from multiple Tribal backgrounds. In considering how best to support our educational mandate it seemed best to focus on the people who have resided in the majority of what is now Vermont since the end of the last Ice Age.

It is therefore exciting to announce that, through a great deal of effort and time, the curriculum is now a reality.

All of the source materials in this curriculum have undergone careful scrutiny by educators and content experts, both Native and non-Native, in order to provide students with a scholastically sound curriculum. It has been constructed using the The College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, GeographyThe study of places on Earth, their features, and the people who live there. , and History, adopted by Vermont Agency of Education in 2017. This framework utilizes critical thinkingA set of skills that requires one to inquire, analyze, interpret, synthesize, and reflect on information to form a comprehensive response. skills and acknowledges, “There will always be differing perspectives…the goal of knowledgeable, thinking, and active citizens, however, is universal.”

Daniel Coutu Chair

Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs

Click + to view the content in the Accordion boxes below. Click – to close the box when done.

Acknowledging Complications of History and Identity

The following information comes from the “Deep Roots, Strong Branches” traveling exhibition, Vermont AbenakiHistorically, this name was used by the French to refer to many different Indigenous communities in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. During the colonial wars, some New England Indians moved to southern Canada as war refugees. They were joined by refugees from other tribes and together became known as Abenaki. (Calloway, 1994) Artists Association, curated by Vera Longtoe Sheehan (2025e).

The IndigenousThe first people living in any region, distinct from later arrivals. people called “Abenaki” have continuously lived in Northeastern North America, in the homelands they call “Ndakinna,” for more than 12,000 years. They have survived and adapted to drastic environmental changes since the “Ice Age” era, when glaciers covered the land. Over time, as the glaciers melted, the region changed from arctic tundra to eventually become the forested lands of present-day Vermont. The area was rich in natural resourcesParts of the environment that people use, such as sunlight, air, water, soil, rocks, fossil fuels, and living organisms. , and people moved seasonally around Ndakinna to utilize various hunting territories and gathering places, many of which were occupied for several thousand years.

Long before European arrival and into the present day, Abenaki people maintained social, economic, and political relationships with other Indigenous people. Some relationships were friendly, marked by trade and alliance, but some were adversarial when resources were at stake. Abenaki family bandA small group of Native American people with its leaders, usually part of a larger tribe. organization was fluid and flexible, and people routinely sought marriage partners in other bands or tribes. The complexity of relationships between Abenaki people and their neighbors continues into the present day.

Before European contact, these people called themselves Wôbanakiak, a name that combines the terms for dawn (wôban) and land (aki) with an animate plural ending (-ak), meaning people “from where the daylight comes” (Laurent, 1884, p. 205). During the mid-1600s, European colonial settlersPeople who come to a new place to live. began using the name “Abenaki” or “Wabanaki” to apply to many different Native American communities, tribes, family bands, and groups across New England (Charest, 2001; Day, 1978; Day, 1981; Fabvre, 1970).

By the late 1600s, French Jesuit missionaries convinced some Abenaki families to relocate to Catholic missions on regional waterways. These included the St. Francis Mission on the St. Lawrence River; Fort Saint-Frédéric on Lake Champlain; and Mission des Loups on the upper Connecticut River, among others. The French built another mission along the Missisquoi River in the mid-1700s. Some Abenaki families embraced mission life and French allies, but others rejected the restrictions imposed by French colonists and missionaries, and returned to their original territories. Clashes between French and English settlers during the “French and Indian War” era in the early to mid-1700s led to the burning of these missions.

Historical marker commemorating the Koas Mission des Loups. Photo by Chief Nancy Milette Doucet. Courtesy, Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki NationPeople living in the same region under its independent government and having a shared history, language, and culture. .

According to the scholar Gordon Day, who worked closely with the communityA group of people living or working together in a particular area, or people belonging to a cultural group. of Odanak in Quebec during the mid-1900s, families from many different tribal groups in central and northern New England sought refuge at the St. Francis Mission on the St. Lawrence River during the chaos of the French and Indian wars (Day, 1981). Some of the families living at Odanak today are descendants of these refugees. Many Abenaki families in Cowass and Missisquoi territory, however, refused French invitations to relocate to Quebec (Calloway, 1991, p.152).

Over the years, Abenaki families made individual decisions about where to live. Some went to Odanak and stayed; others never left their original home places in present-day Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Some families crossed the St. Lawrence seasonally, and returned to living in familiar homelands (Parker, 1994).

Traditionally, Abenaki bands identified themselves by the place names of particular regions in Ndakinna, such as Cowass, Missisquoi, Pennacook, etc. But over time, the Abenaki (like many other Native American tribes and communities on the North American continent) have come to be known, not by their own names, but by names assigned by government officials in the states, provinces, and nations that surround them.

Abenaki people in the United States and Canada continue to have different experiences. In the United States, Abenaki people can hold dual citizenship as U.S. citizens and as Indigenous people. In 2011 and 2012, the State of Vermont formally granted state recognition to four resident Abenaki tribes (Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi, and Nulhegan) with over 6,000 Abenaki citizens. In Canada, tribal nations are governed under a different system called the “Indian Act.” Several thousand Abenaki people associated with Odanak and Wôlinak have what is known as Indian Status (Government of Canada, 2024). There are also Abenaki families living in Ndakinna who are not citizens of any of these tribes. Although all of these people identify themselves as “Abenaki,” the differences among their various locations and relations may create some confusion among outside observers.

For More Information

The sources below can help better understand the complexity and nuances of Native American recognition locally, nationally, and across North America.

Abenaki Region: Comparing Vermont’s State-Recognition

(Related word: recognized): An acknowledgment by a state government when a Native American tribe presents proof that it has existed as a distinct community in that state. Process to Indian Status in Canada

Assembly of First Nations/Assemblée des Premières Nations. (2020). What Does It Mean to Be Registered as a 6(1) or 6(2)? (p.3). Assembly of First Nations/Assemblée des Premières Nations. https://www.afn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/02-19-02-06-AFN-Fact-Sheet-What-does-it-mean-to-be-a-61-or-62-revised.pdf

Bill Status S.222 (Act 107), Vermont General Assembly 2009–2010 Regular Session, 26 V.S.A. (Title 26: Professions and Occupations) (2010). https://legislature.vermont.gov/bill/status/2010/S.222

Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs/Gouvernement du Canada. (2018). BackgroundThe prior knowledge, context, and information the learner needs to understand new content. on Indian Registration. Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs/Gouvernement Du Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1540405608208/1568898474141

Government of Canada; Indigenous Services Canada. (2024). About Indian Status. Government of Canada; Indigenous Services Canada. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032463/1572459644986

Perspectives on Indian Identity

Bergman, Gene. (1993). “Defying Precedent: Can Abenaki Aboriginal Title Be Extinguished by the ‘Weight of History’?” American Indian Law Review Vol. 18, No. 2 (1993), pp. 447-485. https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol18/iss2/4/

Hayssen, Sophie. (2021). “Tribes That Aren’t Federally Recognized Face Unique Challenges: There are almost 400 unrecognized tribes in the U.S.” Teen Vogue, November 24, 2021. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/tribes-not-federally-recognized

Hill, N. S., & Ratteree, K. (2017). The Great Vanishing Act: Blood Quantum and the Future of Native Nations. Fulcrum Publishing.

State Recognition

The Arizona Board of Regents. (2025). Governance Under State Recognition | Native Nations Institute. The University of Arizona Native Nations Institute: Founded by the Udall Foundation & the University of Arizona. https://nni.arizona.edu/our-work/research-policy-analysis/governance-under-state-recognition

Koenig, A., & Stein, J. (2008). Federalism and the State Recognition of Native American Tribes: A Survey of State-Recognized

(Related word: recognition): A title conferred by the state government to a Native American tribe acknowledging that the tribe has existed as a distinct community in the state. Tribes and State Recognition Processes Across the United States. Santa Clara L. Rev., 48, 79.

Ram, K. (2011). Tribal Recognition in Vermont: By Kesha Ram, Vermont State Representative the Role of Federal Standards. Communities and Banking. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 22(1), 7–8.

Salazar, M. (2025). State Recognition of American Indian Tribes. LEGISBRIEF: Briefing Papers on the Important Issues of the Day, 24(39). https://legislature.maine.gov/doc/5373

Introduction to the Curriculum

The American AbenakiAbenaki tribes, families, and people who live in the United States. Vermont has four recognized Abenaki tribes; for more information visit Abenaki Alliance. Curriculum: A Journey of History and ResilienceThe ability of people to recover quickly from a difficulty or to adjust easily to change. (American Abenaki Curriculum) is an interdisciplinaryWhen content and skills from multiple subject areas are presented and practiced together in the same learning experience. curriculum designed using an adaptation of the Inquiry Design ModelThe Inquiry Design Model (IDM) (Swan et al, n.d.) is a distinctive approach to creating instructional materials that honors teachers’ knowledge and expertise, avoids over-prescription, and focuses on the key elements envisioned in the C3 Inquiry Arc. (IDM), with recognizable features such as a Compelling QuestionFrom the Inquiry Design Model (IDM) At a Glance: “Compelling questions address issues in and across the academic disciplines that make up social studies. They reflect students' interests and the curriculum and content with which students might have little experience, Example: Was the American Revolution revolutionary?”(Grant et al., 2014), three Supporting Questions, Summative Performance Tasks, and Taking Informed Action sections. (Swan et al, n.d.) This inquiry1. Inquiry is asking questions, seeking knowledge, and investigating information. According to the C3 Framework, inquiry is at the heart of social studies. 2. A comprehensive curricular unit designed for the C3 Framework that includes the key components of questions, tasks, and sources. The inquiry format leads students through the investigation of a compelling question. differs because we intentionally include a menu of activities for teachers to choose from based on the needs of their students.

Although the American Abenaki Curriculum was developed for students in grades 3 to 5, it has many activities that are suitable for students in grades 6 to 12 to learn about history, living Abenaki cultures, and traditions of the Abenaki people. The American Abenaki Curriculum aligns with the College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework, adopted by Vermont in 2017. It also provides potential alignments with the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts (CCSS ELA), the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Standards, formerly known as the National Educational Technology Standards, and the National School Library Standards for Learners, School Librarians, and School Libraries from the American Association of School Librarians (AASL).

The American Abenaki Curriculum mostly centers on the voices of Vermont’s Native American people, honoring their resilience and their significance in our shared local history. The curriculum also respects all students. Each activity was developed to promote empathy, critical thinking, and broader perspectives. This holistic approach will help students develop culturalRelating to the beliefs, language, traditions, and other ways of living that a group shares. sensitivity and an appreciation for lifelong learning about local Indigenous communities, their history, their experiences, and their contributions here in Vermont and New Hampshire.

As you read this Educator’s Guide you may notice the usage of the terms Native American, Indigenous, Abenaki, and American Abenaki. Abenaki is used for historical references of Indigenous people from this region. American Abenaki is used when we discuss contemporary issues, politics, and cultural practices. With this in mind, Supporting Questions 1 and 2 primarily focus on the past with references to the present, whereas the Compelling Question and Supporting QuestionFrom the Inquiry Design Model (IDM) At a Glance: “Supporting questions are intended to contribute knowledge and insights to the inquiry behind a compelling question. Supporting questions focus on descriptions, definitions, and processes about which there is general agreement within the social studies disciplines, which will assist students to construct explanations that advance the inquiry. Typically, there are 3–4 supporting questions that help to scaffold the compelling question. Example: What were the political changes that resulted from the American Revolution?” (Grant et al., 2014) 3 focus on continuity of culture for the local Indigenous people. We also use the terms Native American and Indigenous in distinct ways: one can be Native American but not specifically an Abenaki living in Vermont or the broader New England area. We use Indigenous and Indigenous peoples as collective nouns that refer to the Abenaki people together with their Native American contemporaries in the region.

The curriculum begins with a Compelling Question and is followed by three Supporting Questions, a Summative Performance Task, and Taking Informed Action.

Compelling Question

To answer the compelling question (How have the Abenaki people survived and adapted to their environmentAll the physical surroundings on Earth, including everything living and nonliving. for thousands of years?), students familiarize themselves with the land and its bountiful resources, Abenaki relationships with the land, their neighbors, and communities. Your students will also learn about Abenaki lifewaysThe customary foods, clothing, shelters, and arts of a people. , such as food, clothing, shelterA place or structure that protects people from the weather. , and arts, and how the Abenaki people have preserved their culture through challenging times.

Supporting Questions

- How do geographic features and the environment affect the daily lives, cultural practices, and relationships of the Abenaki people?

- What are some examples of the significant Abenaki lifeways (food, clothing, shelter, and arts), and how have the Abenaki people adapted these lifeways to their environment?

- How have the American Abenaki people demonstrated resilience and resourcefulnessThe ability to find ways to deal with problems quickly and with imagination. in maintaining their culture from colonial times(Related words: colonial, colony, colonize) The period of American history between the time period when Europeans settled in North America in the 1500s and when the United States was declared independent in 1776. to today?

With a ResourceA source of information for student learning, such as a website, video, library book, poster, or map. Bank, and activities including reading, visual art, group discussions, games, and peer review writing, educators will be able to tailor the content for class and individual student needs. American Abenaki Curriculum: A Journey of History and Resilience celebrates the vibrancy of the American Abenaki experience and its contributions to the region’s culture.

Goals

This curriculum

- presents a well-rounded view of Abenaki culture through various disciplines (history, geography, art, and language arts);

- cultivates respect for the Abenaki people by exploring their contributions and history;

- develops students’ ability to think critically about history, cultural difference(s), and cultural preservationActions taken to protect the beliefs, languages, traditions, places, and objects of a group of people. ; and

- promotes civil discourse through active listening and respect.

Teachers Should Know

As the facilitatorA person who makes an action or process easy or easier. of this curriculum, you will provide support, guidance, and feedbackWhat an educator or someone with knowledge provides a learner in response to their demonstrated learning. Feedback helps the learner understand what they have done well and how to improve. to help students engage with the activities and develop an understanding of Abenaki culture and the resilience that Abenaki tribes and families have demonstrated throughout history and in modern times. Understanding Abenaki experiences over a long period of time will help students appreciate American Abenaki perspectives in the present. This section will introduce you to some of the structural features of the curriculum.

Historical Context

Each of the main sections (Compelling Question and Supporting Questions 1–3) contains “Historical Context” essays. The purpose of these Historical Context essays is to provide teachers with background on the topic and provide sources for more information.

Sample Student Responses

Boxes labeled Sample Student Responses highlight common student responses. However, they do not include every possible response students may have. The Historical Context essays and Resources may suggest additional responses.

Sharing of student prior knowledge is welcome, especially from Abenaki students or other students who may have attended a contemporary program or Abenaki heritage(Related term: cultural heritage) Something that is inherited from previous generations and passed along to future generations. It includes family identity, cultural practices, values, and traditions. event. If you have Abenaki students in your classroom, they may volunteer answers but please do not pressure them to act as experts.

The Resource Bank section of this Educator’s Guide presents a collection of Abenaki historical and cultural information to be used with the curriculum activities. All of these resources were vetted by the American Abenaki community specifically for usefulness in this curriculum. The Resource Bank also includes links to Tribal websites, non-profits, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) where more valuable information about Vermont’s Abenaki people today can be found.

The Resource Bank is divided into two sections: Illustrated Resources by Type and Resources by Subject Area With Grade Levels.

Illustrated Resources by Type includes resources categorized as graphics, books, videos, websites, and so on. Each resource listed includes a brief description, keyword(s), and an illustration of the resource. See examples below.

Resources by Subject Area With Grade Levels is a table that you can quickly scan by subjects/keyword(s) or by grade level. See example below.

Recommended Prior Student Knowledge

Students should have some baseline knowledge before they begin this inquiry. You may want to open a discussion by asking whether students know the name Abenaki or have ever attended an Abenaki event or visited an Abenaki exhibit. Students should also know, or be introduced to, the following concepts:

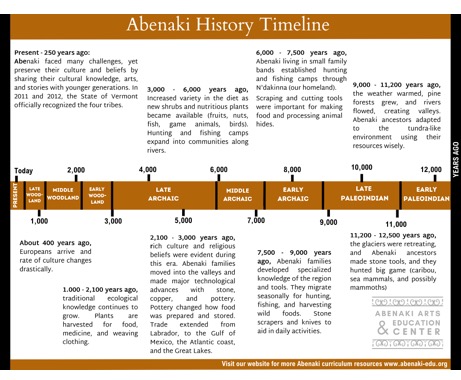

- Understanding the distant past can be challenging. You can use the Abenaki History Timeline (Abenaki Arts & Education Center, 2023) below to introduce the conceptAn abstract idea, a mental construct, a name, or label that helps people make sense of the world. of 12,000 years of history to your students. It summarizes important changes in the living conditions experienced by Abenaki people and their neighbors in northeastern North America over the past 12,000 years.

Abenaki History Timeline. Courtesy of the Abenaki Arts & Education Center. A timelineA graphic representation that shows a chronology of events (in the order they occurred) on a line. poster may be downloaded at Abenaki-edu.org. (Abenaki Arts & Education Center, 2023) - The concept of colonization is necessary to understanding Abenaki resilience after European colonizers arrived from France, England, and other countries. Europeans arrived in the region a little over 400 years ago. Compared to the timeline of Abenaki occupation of the region, that is a very short time.

- Abenaki people today have varied formal Tribal political organizations.

- In Vermont, we have four distinct State-Recognized tribes (Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi, and Nulhegan).

- There are also two Abenaki Tribes in Canada (Odanak and Wôlinak).

- The Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi, and Nulhegan Abenaki Tribes came together to form the Abenaki Alliance, meaning that the tribes are friendly and work to support one another. Learn more at abenakialliance.org/. (Abenaki Alliance, n.d.)

Teacher Tips

- Teachers can introduce the word resilience and other new vocabulary at the beginning of the activities or projects. For example, some 4th graders are familiar with the word resilience and know it as the ability to “bounce back” after something happens.

- It is important to acknowledge Abenaki living culture today. You should strive to speak about the Abenaki people and culture in the present tense. You should also encourage your students to do the same.

- In the Jigsaw activity, we replaced “Expert Group” with “Research Group” because students will not become experts by participating in this activity. Dr. Aronson’s version of the activity calls on students to synthesize what they have learned and teach their “Home Groups” (The Jigsaw Classroom).” (Social Psychology Network, 2025) We ask that students not make generalized statements about Native American people as this is not culturally sensitive. Instead they make observational statements that rely on facts and evidence from research, and they do not include personal interpretation.