“The end of the glacial period in North America . . . brought with it momentous changes. . . Many of the animals on which Paleoindians had depended for food, clothing, and shelterA place or structure that protects people from the weather. were no longer available to them.” —William Haviland and Marjorie Power. From The Original Vermonters: Native Inhabitants, Past And Present. 1994.

You may be wondering what AbenakiHistorically, this name was used by the French to refer to many different Indigenous communities in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. During the colonial wars, some New England Indians moved to southern Canada as war refugees. They were joined by refugees from other tribes and together became known as Abenaki. (Calloway, 1994) people living in Vermont today have in common with their ancestors. The answer is “more than you might think.”

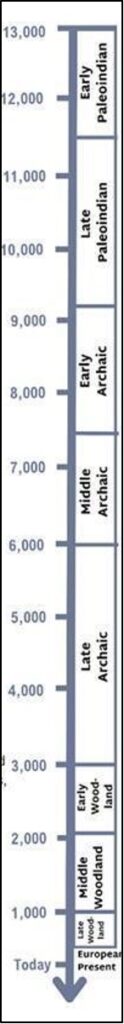

The timeline shown can serve as a reference tool for tracking the adaptations in Abenaki foodways.

Abenaki Paleoindian ancestors, approximately 11,000 years ago, lived in a tundra environmentAll the physical surroundings on Earth, including everything living and nonliving. and relied on hunting large game animals (such as mastodons and caribou), sea mammals (such as whales), and anadromous fish (such as salmon and shad) for their survival. As the temperature rose during the Archaic period, approximately 8,000–9,000 years ago, glaciers retreated, and spruce and pine forests advanced into the region. Climate change also brought a wider variety of animals, shellfish, reptiles, and waterfowl to the region. Archeologists involved with Glacial Kame archeological sites (such as the Ewing Site in Shelburne) have found the remains of “bear, deer, turtle, fish, dog, [and] mussel” (Vermont Historic Preservation, n.d., p. 16).

The warming climate caused other changes in food resources. “By 7000 b.c., over 100 species of large mammals, such as the mammoth, mastodon, and moose-elk, became extinct. Others, like the caribou and musk ox, moved north with the tundra” (Haviland & Power, 1994). In place of these large animals, people turned to hunting other species, such as moose, beaver, lynx, and muskox, while also fishing for whitefish, and catfish.

Rising temperatures also gave rise to beech, birch, and maple trees, which are characteristic of the deciduous forests that Vermont and New Hampshire are known for. Three thousand years ago, the average temperature in Vermont was slightly warmer than today; this warming climate trend during the mid-Archaic period made for greater biodiversity. The variety of animals, nuts, fruits, and edible plants available to Archaic hunters and gatherers is remarkably similar to what we have today (Haviland & Power, 1994).

By the Woodland period, people shifted their lifewaysThe customary foods, clothing, shelters, and arts of a people. , by living in relatively fixed settlements throughout the year. Smaller groups still came together to travel to smaller camps, where they hunted, fished, and gathered seasonal plant foods and medicines for their communities.

By roughly 1,000 years ago, a food plant imported from the Southwest – corn (Zea mays, also called maize) – was being cultivated in both Vermont and New Hampshire (Haviland & Power, 1994, p. 142). As just one example of the archaeological evidence, seven storage pits for corn were found at the Skitchewaug site (date to 1100 CE), demonstrating the importance of corn in the southern Connecticut River Valley diet (Mathewson, 2011, p. 29; Heckenberger et al, 1992; Haviland & Power, 1994, p. 86).

Corn made its way into the Champlain Valley around 1440–1700 CE (Bumstead, 1980; Haviland & Power, 1994). Beans, and squash also appeared in Vermont around the same time. During his regional travels in 1609, French colonial explorer Samuel de Champlain reported seeing “fertile fields of maize” (Heckenberger et al., 1992; Haviland & Power, 1994).

Abenaki people in Vermont continue to practice significant traditional hunting, fishing, and foraging lifeways in a culturally distinct way today; evidence of these practices (confirmed by independent scholars) can be found in the reviews of Tribal petitions for State-Recognition

(Related word: recognized): An acknowledgment by a state government when a Native American tribe presents proof that it has existed as a distinct community in that state. . Abenaki Tribes testified to ancient agricultural practices passed down in families, such as growing crops like corn, beans, and squash in mounds, and a shared culturalRelating to the beliefs, language, traditions, and other ways of living that a group shares. tradition

(Related word: traditional): A way of doing things passed down from generation to generation. of using “suckers” or “kikômkwa” (meaning “the garden fish”) as fertilizer. These skills are still part of the living memory and practices of families from the Elnu, Missisquoi, Koasek, and Nulhegan Abenaki Tribes, who vividly remember learning these traditions when they were children. (Elnu Abenaki Tribe(Related word: Tribal): A group of families or villages that share the same language, traditions, and ancestors. , 2010; Koasek Traditional BandA small group of Native American people with its leaders, usually part of a larger tribe. of the Koas Abenaki NationPeople living in the same region under its independent government and having a shared history, language, and culture. , 2010; Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk-Abenaki Nation, 2010; Abenaki Nation of Missisquoi, 2011).

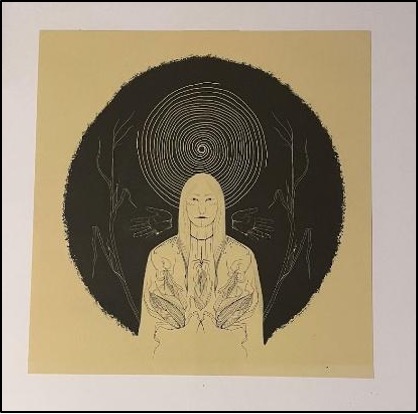

The addition of corn to the list of Abenaki food staples is immortalized in the story of “Corn Mother and First Man,” a story of love where the corn spirit sacrifices herself to feed the people. This story is still told after the “Green Corn Song” echoes through the mountains during the Elnu and Nulhegan Abenaki communities’ annual Green Corn events each August. The Corn Mother is commemorated, not just in song, but also in artwork by contemporary Abenaki artists. The importance of corn as a traditional food is reflected in the children’s book “Little Deer and the Sacred Corn,” by Chief Shirly Hook of the Koasek Abenaki Tribe (Calabro, 2023).

Traditional cultivation of food plants involves year-round seasonal cycles of planting, harvesting, and seed-saving techniques. Over time, some traditional heirloom plants were supplanted by newer commercial varieties.The Seeds of Renewal Project: 2013 Harvest poster (Wiseman, 2013), illustrates Abenaki corn, beans, squash, pumpkin, and sunflower varieties that have been restored to active cultivation by Vermont Abenaki people. Collectively, these traditional crops, together with Jerusalem artichokes (sunchokes) and tobacco, are now known as the Abenaki “Seven Sisters.”

For More Information

Bumstead, M. P. (1980). VT-CH-94 Vermont’s earliest known agricultural experiment station. Man in the Northeast, 19, 73–82. [hard to find article can also be found at https://13c4.wordpress.com/2006/01/09/vt-ch-94-vermonts-earliest-known-agricultural-experiment-station/]

Haviland, William A. and Marjory W. Power. (1994)The Original Vermonters: Native Inhabitants, Past and Present. (Revised and Expanded Edition). University Press of New England.

Wiseman, F. M. (2001) The Voice of the Dawn: An Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation. University Press of New England.

Wiseman, F. M. (2006) Reclaiming the Ancestors: Decolonizing a Taken Prehistory of the Far Northeast. University Press of New England.

Wiseman, F. M. (2018). Seven sisters: Ancient seeds and food systems of the Wabanaki people and the Chesapeake Bay region. Earth Haven Learning Centre Incorporated.

The above information comes from the “Deep Roots, Strong Branches” traveling exhibition, Vermont Abenaki Artists Association, curated by Vera Longtoe Sheehan (2025e). Printed with permission of the author. Share as much or as little with your students as needed to successfully complete the curriculum activities.

©2025. Vera Longtoe Sheehan. All Rights Reserved.